Classifying images of Mars with a Convolutional Neural Network

Published:

Background

The successful landing of NASA’s Perserverance rover yesterday marks the fifth chapter in NASA’s rover program, which began sending rovers to Mars in the late 1990s. None of these missions would have been possible without the Mars orbiters, which NASA and the Soviet Union (and ESA, more recently) started sending as far back as the 1970s. The orbiters are used to map the surface to find optimal sites for the rovers to land and then explore. They also communicate with the rovers during their missions to help them navigate and send and receive data to and from Earth. While it may seem as though their sole purpose is to faciliate the rover missions, the orbiters are important in their own right. They generate the most detailed images that humanity has captured of another planet. Until I started looking at these images, I really did not appreciate how diverse and rich the Martian surface is.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter contains HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment), the “most powerful camera ever sent to another planet,” according to the instrument homepage. This camera takes images of Mars at extremely high resolution (< 1 meter/pixel) and has been taking data since 2006. As a result, this has generated an enormous amount of high quality image data, and the HiRISE team has been kind enough to make a lot of it public. Based on the variety of surface features present in the images and the size of the dataset, I thought it would make an interesting and challenging dataset for feature detection with a convolutional neural network (CNN). Because I was not able to find a prepackaged dataset of the Martian surface on sources such as Kaggle, I decided to create one from the HiRESE image database myself.

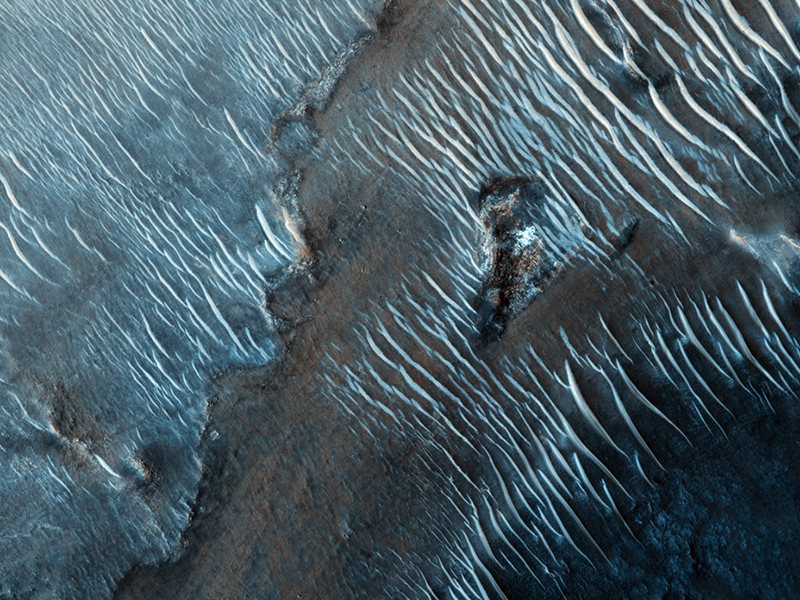

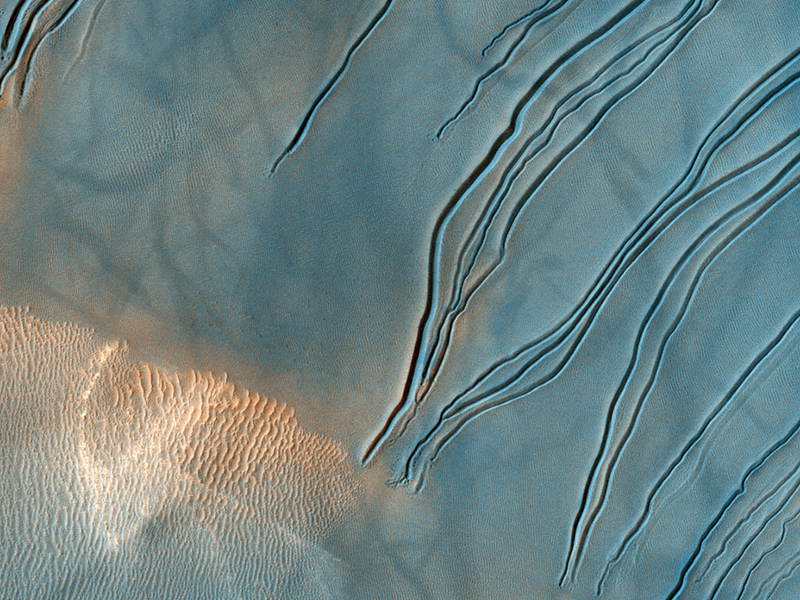

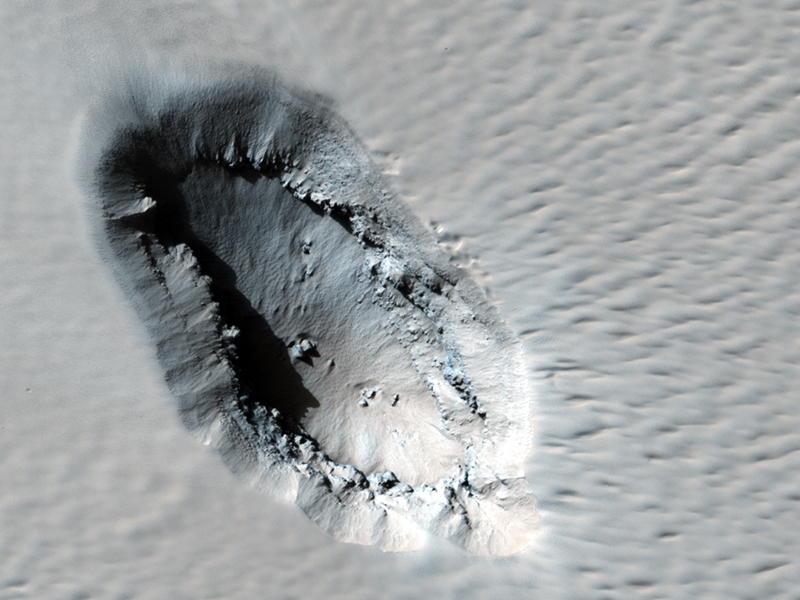

Images of the Martian surface taken by the HiRISE camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Setting a goal

My ultimate goal is to train a CNN to classify images of the Martian surface by features such as dunes, craters, polar ice, ancient river deltas. This is considered a multi-label, multi-class classification problem because each image can have more than one class label. For example, an image can have both dunes and craters in it. Such problems are more complicated than single-label, binary classification problems, such as determining whether an image is of a dog or a cat.

I figured that if I could not get good performance on a single-label binary classification problem given this dataset, then I would have no hope on the multi-label problem. So I set an intermediate goal to train a CNN to classify whether the images had craters in them. This is a single-label binary classification task because the image either contains craters or it does not. I chose craters as a first step because they are geometrically simple and they are in enough of the images to make a relatively large dataset for training, validating and testing the model. My goal was to assemble a dataset of 2400 images total, with 1200 images for each class (crater or no crater). This is on the small side for a CNN, which can consist of millions of parameters. The CIFAR-10 dataset, for example, contains 6000 images for each object class (e.g truck, airplane, automobile).

The dataset

HiRISE provides ~2000 high-resolution RGB images of Mars with metadata and about 66,000 (at the time of writing this) additional images without metadata. The images were taken from all over the surface of the planet and at many different times of sol (the name for a day on Mars). The metadata capture the time and location that the image was taken (among others) so I thought it would be interesting to look at model performance as a function of these parameters. The notorious dust storms that make seeing the surface (and communicating with the rovers) difficult are absent from these images. Mars’ atmosphere is very thin compared to Earth’s so clouds do not affect the image quality as they often do in Earth satellite imagery. Finally, the images are taken at approximately the same altitude, so the scene size (and pixel size) is similar among all of the images.

I downloaded the ~2000 images that have metadata from here: https://static.uahirise.org/images/wallpaper/. The images are provided in various resolutions, but I chose the lowest resolution, 800x600 pixels. I planned to downsample the images to a lower resolution than this anyway. I scraped the metadata from their html pages which they make available here: (https://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/) using beautiful soup.

After looking through a random subset of the images I noticed that only about 10% of the images had craters in them. This meant that I was not likely to meet my goal of labeling 1200 images with craters for training/validation/testing. Fortunately, the scenes are large and often contain multiple craters per image when craters are present. I was able to chunk each image up into 12 square sub-images, resulting in a total of ~24000 200x200 images. About 5% of these smaller images contained craters, so this enabled me to just about meet my dataset size requirements.

Making the training set

While the image metadata contain a text description of the scene, the description is not sufficient for labeling whether an image has a crater in it. This becomes especially true after dividing each original image into 12 sub-images. As a result, I decided to label the images manually by visually inspecting them.

I created a Flask application to make inspecting and labeling the images as quick and painless as possible.

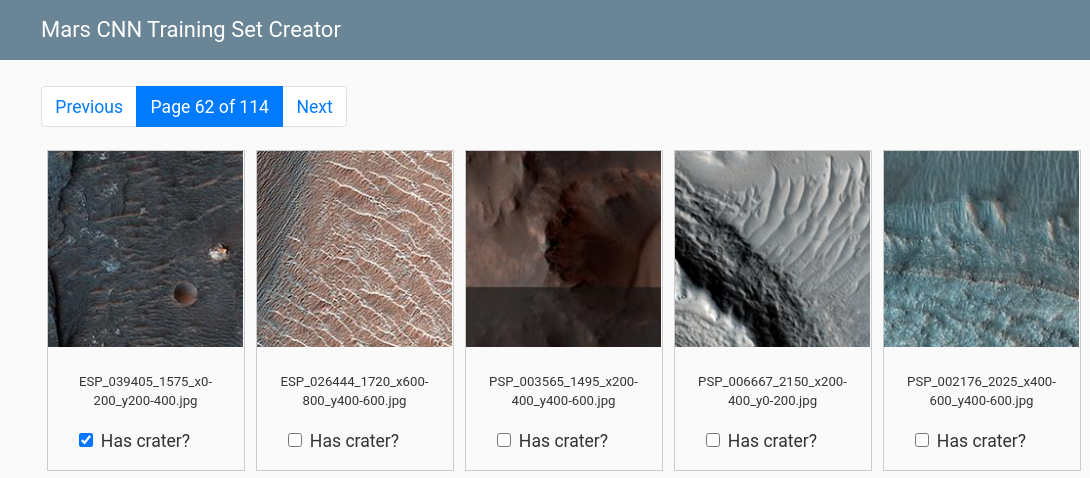

A screenshot from the Flask application I developed to quickly label images with craters in them for training the CNN

I set up the application so that clicking anywhere in the image would select a checkbox indicating whether the image contained a crater. Each page is an html form that when submitted updates a CSV file to record the image labels. I paginated the display so that each page had 100 images. This allowed for fast page loading and form submission times. I was able to look through a page of 100 images and label them in under a minute, so the whole process ended up taking me a few hours one afternoon.

Craters come in a wide range of sizes, but they are primarily circular. In deciding on which images contained craters, I had to make a few choices which I knew would influence how the model learned and ultimately performed. On my first pass through the data, I decided to label anything that I thought belonged to a crater of any size. This included very small craters and craters that were so large that only a fraction of them was visible on the screen.

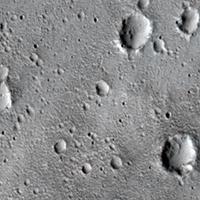

Left: An image with several obvious, medium sized craters. Middle: a portion of a very large crater wall. Right: several very small craters. In my initial training/val/test sets, I labeled all of these images as having craters. In my second pass, I only used the left image.

As I will show, this ended up being overly optimistic. A smaller training set with a stricter definition of a crater ended up outperforming my initially trained model.

Choosing a model

I tried several custom models, starting with a very simple CNN architecture consisting of only a few hidden layers. Here is a simple model I implemented with tensorflow/keras:

def make_model(input_shape):

inputs = keras.Input(shape=input_shape)

x = layers.experimental.preprocessing.RandomFlip("horizontal")(inputs)

x = layers.experimental.preprocessing.RandomRotation(0.1)(x)

outputs = keras.Sequential([

layers.Conv2D(32, 3, padding="same",activation='relu',input_shape=input_shape),

layers.MaxPool2D(pool_size=(2,2), strides=2),

layers.Conv2D(64, 3,padding="same",activation='relu'),

layers.MaxPool2D(pool_size=(2,2), strides=2),

layers.Flatten(),

layers.Dense(units=1,activation='sigmoid'),

])(x)

model = keras.Model(inputs, outputs)

return model

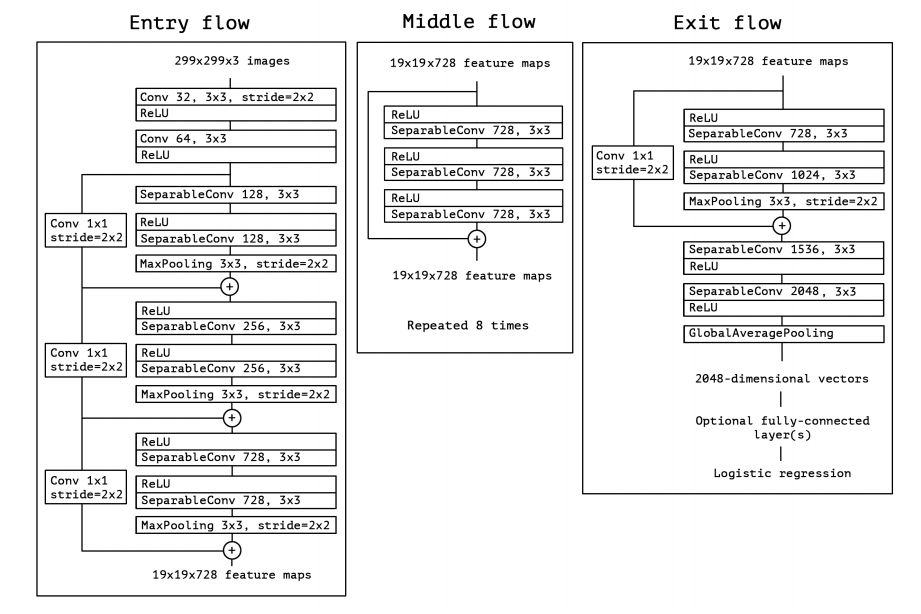

I found that such models were unable to reach over 60% accuracy on the validation set. I also tried some established architectures and found that a modified version of the Xception network performed best. Xception is a modification of the Inception V3 model, where the main difference is the order of the depth-wise and point-wise convolutions is flipped in the Inception module. I found this post helpful in illustrating the difference: https://maelfabien.github.io/deeplearning/xception/#the-depthwise-convolution. Xception outperforms most other popular CNN networks such as Inception V3 and VGG-16 on standard image classification challenges like ImageNet. The architecture of the full Xception model is shown below:

The Xception network (Chollet et al. 2017)

I used a keras implementation of a small version of this network which essentially skips the middle flow: https://keras.io/examples/vision/image_classification_from_scratch/. This model performed a lot better than the full Xception network which suffered from overfitting when I tried it on my dataset.

One of the drawbacks of Xception is that it can be computationally expensive to train (but not significantly more so than many competitors). However, the smaller version of the model I ended up using has ~10x fewer parameters (total 2,782,649 parameters) than the full network.

Training the model

I split the ~2400 images in my labeled dataset into ~1600 for training, ~400 for validation and ~400 for testing. I also downsampled the images to 180x180 to speed up training.

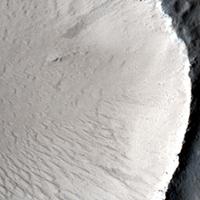

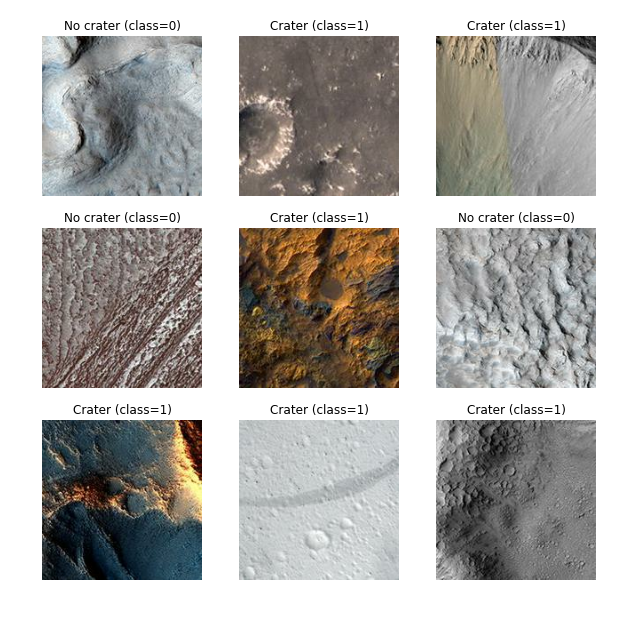

Examples from my first pass training set

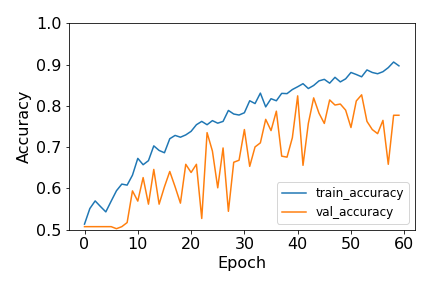

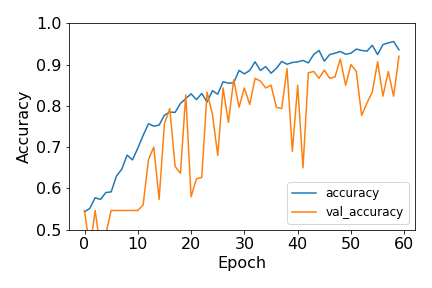

I used a batch size of 32 and trained the model over 60 epochs. Training took ~30 minutes on 12 CPUs (I didn’t have access to GPUs at the time).

Accuracy of training and validation sets of the Xception model over 60 epochs of training using my first-pass training set.

The variance in the accuracy curves is a clear indication that especially my validation set of 400 images is on the small side for the diversity of the images in the dataset. Varying the hyperparameters like learning rate and batch size did not significantly decrease the variance of the training loss/accuracy. That said, the overall trend is clear: the validation accuracy increases until about 40-50 epochs, after which it decreases while training accuracy continues to increase – a tell-tale sign of overfitting. The maximum validation set accuracy is 83% at epoch 53, so I chose this epoch as my best-fit model.

Model performance

The best-fit model has an accuracy of 78% on the test set. This is not too bad, especially given the limited size of the training set, but it could definitely be improved.

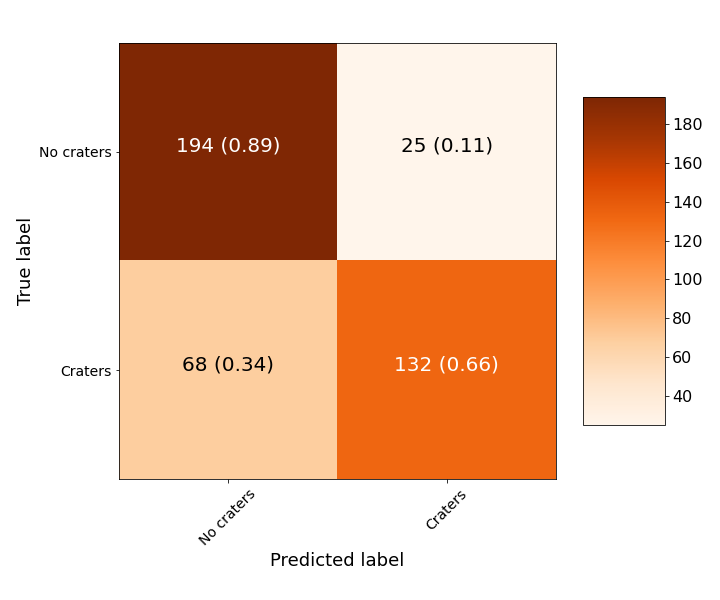

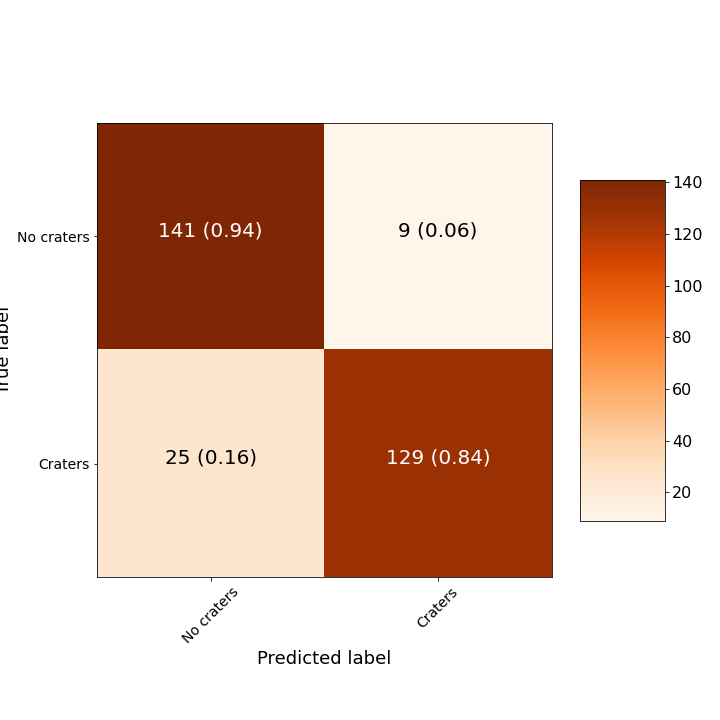

To get more insight into where the model could use improvement, it is useful to look at the confusion matrix:

Confusion matrix of Xception model trained using first-pass training set. Each cell contains the total number of predictions in the category followed by the fraction in of predictions in that row.

The model has good precision but not very good recall. In other words, the model can pick out when an image does NOT contain a crater much better than when an image contains a crater. In an analogy with testing for the presence of a virus (where 0=no virus and 1=virus), if a test had our model’s confusion matrix told you that you had the virus you could be 89% sure it was correct. However, if it told you you didn’t have the virus, you could only be 66% sure it was correct. When put that way, it is clear this is far from a perfect model. Let’s look at some image examples of false negatives, i.e. where the model predicted no craters but there were in fact craters:

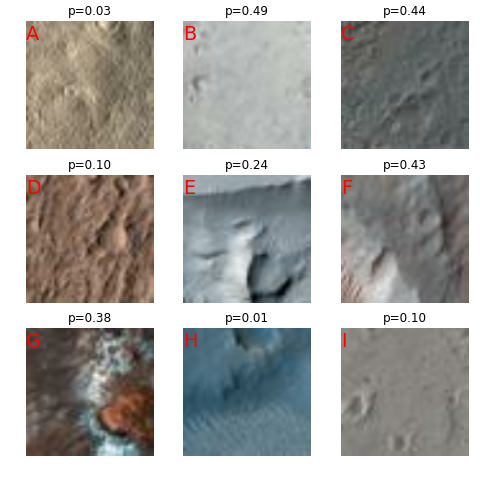

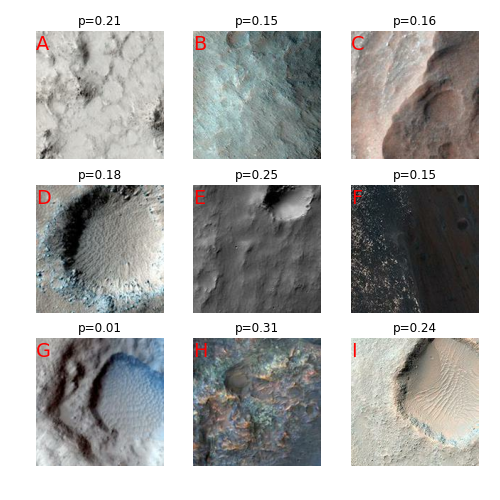

Nine example test-set images where the model predicted no crater but the image was labeled as having a crater(s) (from the first-pass dataset). The model-predicted probability that the image contained craters is listed above each image.

In a few of these images, such as images A, C and G, the craters are not obvious even to the human eye, especially at this resolution. In image H, the crater is only partially visible. Probabilities close to 0.5, as in images B, C, F and G indicates that the model was ambiguous about these images. At this point I decided that if I wanted a model with better performance, a good idea would be to clean up the dataset that I was using for training, validating and testing the model. I worried that dropping too many images would make my small dataset even smaller, but it was a test worth doing.

Re-training with a cleaner dataset

I went back through the train/val/test datasets and removed labeled images from either category that had partial or inobvious craters. Fortunately I had not exhausted the entire dataset in my first pass, so I had new images in which to find obvious craters. This partially balanced out the fact that I removed a significant number of images with inobvious or incomplete craters. I made sure that none of the images that I discarded as being too inobvious ended up in the no crater class of the cleaner dataset.

I ended up with a cleaned dataset consisting of 2100 images, which I split into 1500 for training, 300 for validation and 300 for testing. This was smaller than I had hoped, but it would at least allow me to test whether dumping the dirty data would improve the model, as I expected. I retrained the same Xception model on the cleaner dataset using the same batch size (32) and number of epochs (6) as before.

Accuracy of training and validation sets of the Xception model over 60 epochs of training using my cleaner dataset.

The result was significantly (>~10%) better than the first pass on the validation set, despite having a 12.5% smaller dataset. While I was not surprised to see an improvement, the magnitude of the improvement was very encouraging. The accuracy of the validation set increased on pace with the training accuracy for all epochs. This indicates that overfitting never became an issue. The maximum validation set accuracy of 92% came on the final epoch, 60, so I chose this epoch as my best-fit model. The noisiness in the validation accuracy curve is a clear indication that especially my validation set of 400 images is on the small side. Still, the general trend of the model is clear.

Model performance (cleaner dataset)

Using the best-fit model from epoch 60, I found a test-set accuracy of 89%. This is much better than I was expecting starting out with this project. It encouraged me that I could at least attempt multi-label/multi-class classification on these images. This also underscores the maxim that “better” data is more valuable than more data.

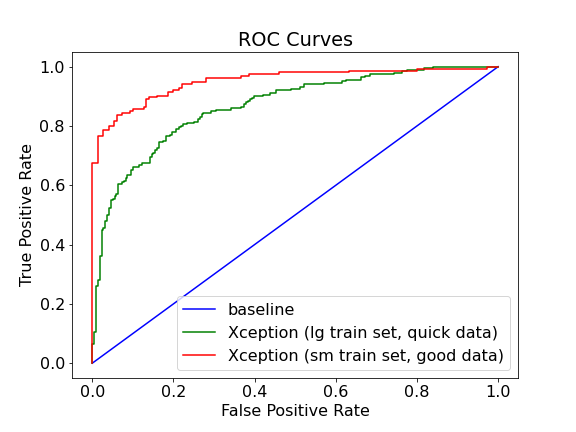

The classes are balanced in this dataset, so accuracy is not a biased measure of model performance. Still, accuracy is a blunt measurement and I prefer the ROC curve and confusion matrix for model comparison.

ROC curves for the two Xception models using different datasets compared to the baseline of randomly guessing class membership. The green curve is the Xception model I ran using the larger, first-pass dataset and the red curve is the same model ran on the 12% smaller dataset but with much cleaner data.

As with the accuracy, the ROC curve shows the clear improvement in performance after cleaning up the dataset. The ROC area-under-curve (ROC AUC) score for the green curve (first-pass dataset) is 0.87 whereas for the green curve (cleaned dataset) is 0.95, a very good score – a perfect model has a score of 1.0. Finally, we can examine the confusion matrix for the better model to see where it could be improved:

Confusion matrix of Xception model trained using cleaned (second-pass) training set. Each cell contains the total number of predictions in the category followed by the fraction in of predictions in that row.

As with the previous model, the model has much better precision than recall. It still struggles to detect all of the images with craters. Let’s look at some examples where this happened, i.e. false negatives:

Nine example test-set images where the predicted no crater but the image was labeled as having a crater(s). The probability that the model predicted that the image contained craters is listed above each image.

Images B, D, E, G and I are all incomplete craters which I failed to remove from my dataset during the cleaning process, so I suspect that is at least part of why they are not predicted as craters. The craters in A, F and H have low contrast compared to the background of their image, so that could explain why the model had a hard time picking them out.

Beyond craters

My single-label, single-class model to determine whether craters were present or absent in the HiRISE images was successful enough to warrant an attempt at a more complicated problem: discerning whether the images contained dunes and/or craters. This is considered a multi-label, multi-class classification problem because each image can contain 0, 1 or 2 labels. For example an image can either contain neither dunes nor craters (0 labels), craters but not dunes or dunes but not craters (1 label), or both craters and dunes (2 labels).

From the modeling standpoint, not much needs to be modified to turn this into a multi-label classification problem. I simply need to add another unit to the final Dense() layer of my network so that the network has two outputs instead of one. I was already using a sigmoid activiation function for the single-label binary classification case in this final layer, and that is still the preferred activation for the two-label case as well. In this case, the labels will be 2-vectors where each element represents the probability that the image contains craters (0th element) and the probability that the image contains dunes (1st element). Those probabilities are then rounded to 0 or 1 to make the predicted label.

Most of the work will be in preparing the training set, which now needs to consist of images that contain dunes as well. I created a new page in my flask application for labeling dunes, like the page I used to label craters. I reinspected all ~900 of the images that contained craters and found that 31 of them also contained dunes. I labeled an additional ~900 images with dunes only to match the number of images with craters only. I also labeled a new set of ~900 images that contained neither craters nor dunes.

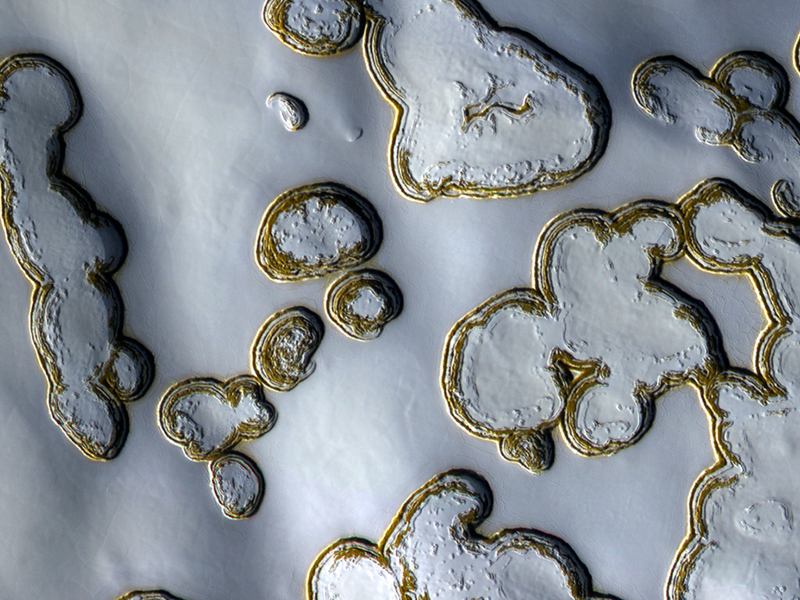

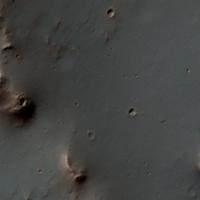

Three images I labeled as having dunes in the HiRISE dataset. The middle image is one of ~30 images which contain both craters and dunes.

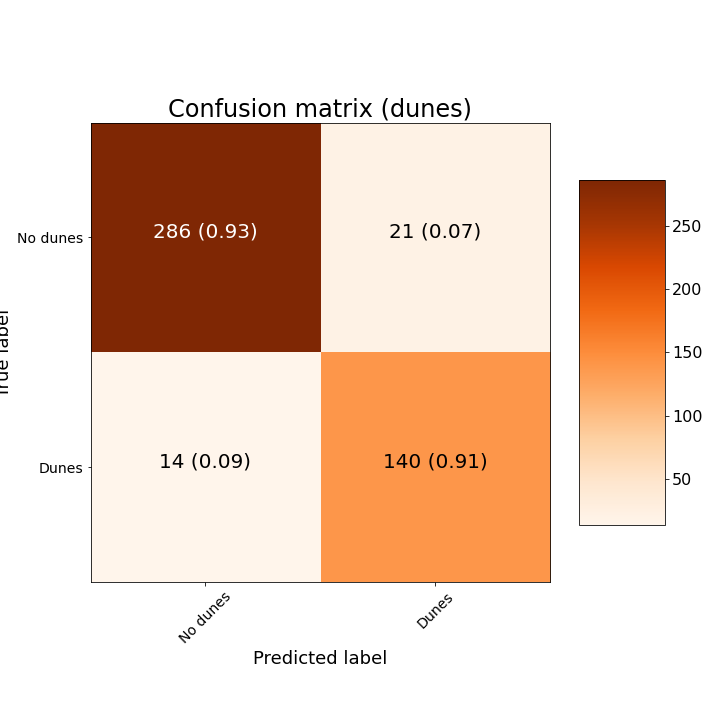

My final dataset consisted of 1775 training images, 444 validation images and 461 test images. Using the same network and training parameters, I achieved a max validation accuracy of 93% after 56 epochs. Adopting this as the best-fit model, I achieved a test-set accuracy of 92%, which outperformed my single-label model. The reason this model has better accuracy is because it turns out to be easier for the model to pick out dunes than craters. Below is the confusion matrix for dunes from this model.

Confusion matrix for dunes from the multi-label test dataset.

The confusion matrix for dunes shows good precision and recall. The confusion matrix for craters is approximately the same as it was for the single label case.

Visualizing the learning process

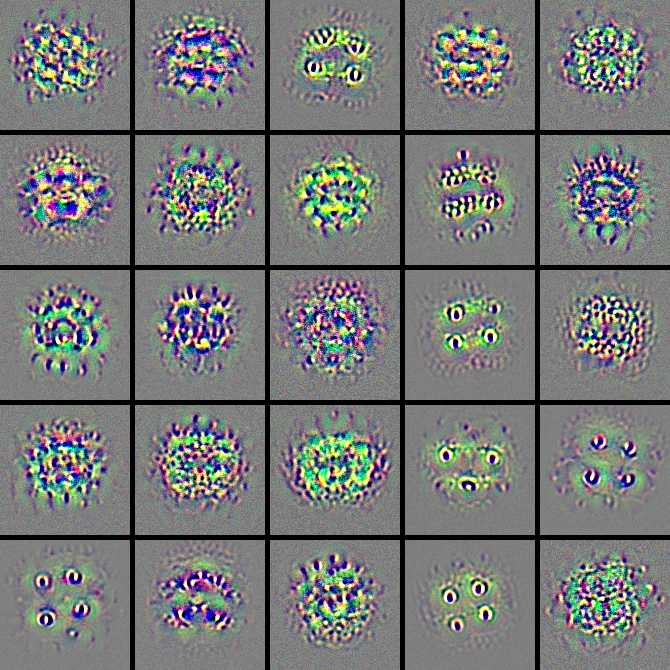

Large neural networks like Xception can seem like black boxes. One way to probe what they are actually doing is by visualizing the filters that are learned during training. This is straightforward to do using Keras, e.g.: https://keras.io/examples/vision/visualizing_what_convnets_learn/. Let’s apply this to one of the final Conv2D layers in my best-fit multi-label model:

The first 25 learned filters from one of the final convolutional layers of my Xception model.

As expected, the filters consist of many circular patterns and linear striped patterns. These allow the model to successfully pick out craters and dunes, respectively. Interestingly, the filters containing circular patterns typically come in multiples rather than a singular large circle. This may explain why the model’s false negatives (cases where the model was unable to predict that an image contained craters) were primarily images with only a single crater.

Acknowledgments

The HiRISE images used in this project are within the public domain. A huge thanks to NASA/JPL/University of Arizona for making the images available and easily accessible.

I used Keras, a deep learning library, for building, training and evaluating my CNN models.

Here are some related articles that I found helpful when writing this: